Although first coined in 2017, most of us are now aware of a new term in our lexicon – ‘cancel culture’. That is, withdrawing support for people and companies for doing or saying something seen as objectionable or offensive. It is usually performed on social media in the form of group shaming.

Communications practitioners have a long history of dealing with these types of reputational issues with high-profile individuals and companies. Using various techniques, our role has been to provide advice during a crisis, manage media channels and to develop a plan to restore the brand over time.

Despite our experience in dealing with crisis, some might argue cancel culture is a new paradigm. In most cases, online movements are partisan, passionate and organised, which ensures they are loud and influential. But what makes them so powerful is their single-minded focus on their only objective – to cancel you.

So, what do you do when your company or brand becomes the target of the online mob?

Firstly, it is impossible to miss. Your social feeds will start clogging up with detailed posts defining what your company has done wrong and how individuals feel about this wrongdoing. This information will be helpful because it will help you define the issue and impact that it has on your customers, staff and stakeholders.

Of course, it is easy to panic when this happens. It may be difficult to see the curated online platforms your brand uses to promote itself being used against you, but don’t shut the conversation down – this will only make people angrier. Only hide those comments that breach your published social media guidelines. You are then justified in removing comments that are obscene, offensive, defamatory, threatening, harassing, discriminatory or hateful – which they often can be.

These campaigns will usually be driven by perceived wrongdoings by your company that were perpetrated recently, or even in the long-distant past. It would be a mistake to assume these concerns as the rantings of a small splinter group.

At this point, you should assess whether this is a crisis that could have a lasting impact on your brand. This may seem hyperbolic, but if you are facing an online cancel campaign, it is difficult to assess how powerful these invisible adversaries are. And if you handle your response poorly, your brand could be under unrelenting attack, so consider activating your crisis plan. In any crisis we follow the Three C’s Model of Care, Control, and Commitment.

As your social channels continue to be flooded with negative commentary, there is a natural temptation to defend yourself. Don’t. A defensive response – no matter how politely it is framed – is likely to be attacked as unfeeling and unsympathetic to those who have been wronged. You won’t have had time to collect all the information you need, and you can’t go back on your words.

Rather than responding to every post in public forums (you will be trolled) find a way to communicate with advocates offline. In many cases, it’s not actually clear exactly who is doing the cancelling. From drag queens losing gigs after past appearances in blackface to obscure Dr Seuss books being voluntarily pulled by their publisher for racist imagery, sometimes these campaigns take their own shape without specific leadership.

Even if there is no campaign organiser, there will be influencers in this space who might be willing to talk to you. Once you have built up a network of sorts, make an effort to understand their concerns, how they prefer to communicate, and what they would like you to change.

It is at this point that you should consider your response. If you need to apologise, then say ‘sorry’ and acknowledge each concern. A senior leader should be prepared to make this apology, it should be heartfelt, and it should be done by video – which works to show your human side and the ‘Care’ your organisation feels for the breach.

Of course, sorry may not be enough – even if you don’t have all the answers now, outline a process your company will undertake to investigate the issue to ensure it doesn’t happen again – this is the ‘Control’ phase of our crisis approach.

In the case of the destruction of culturally-significant caves at Juukan Gorge, Rio Tinto undertook a complete review of, what it calls, a breach of their values. After apologising unreservedly, it acknowledged and investigated each of the errors that occurred, and completely reviewed their processes to “ensure this never happens again”.

Public opinion and shareholder pressure eventually saw the departure of senior executives, but the organised online outrage remains. Following the Care and Control phases, Rio Tinto reached out to partners, including the Traditional Owners, to understand concerns, to address these concerns, and is taking a sensible long-term view of restoring its brand.

The ‘Commitment’ phase in crisis management takes time. But only in the last week, the PKKP people have shown a conciliatory approach to Rio Tinto by insisting on a seat at the table for any mining activities on their land.

For less egregious breaches of trust, it is not always obvious how you should respond to public cancel campaigns. It’s not even clear what “being cancelled” means for a brand exactly, other than having to pay an economic cost after an offensive statement or action. Is Dr Seuss really cancelled? After the campaign to remove racially offensive books resulted in them being pulled, sales surged to record levels.

After attempting to understand the issues raised by online campaigners, have a chat with your staff and customers. Your staff want to be proud of where they work, and they won’t want you to apologise or give in to what they might see as unreasonable demands. Communicate with employees so they might see the perspective of the campaigners, and openly consult with them about your response. In the end, staff and customers can also be organised as an army of advocates to see off any online campaign.

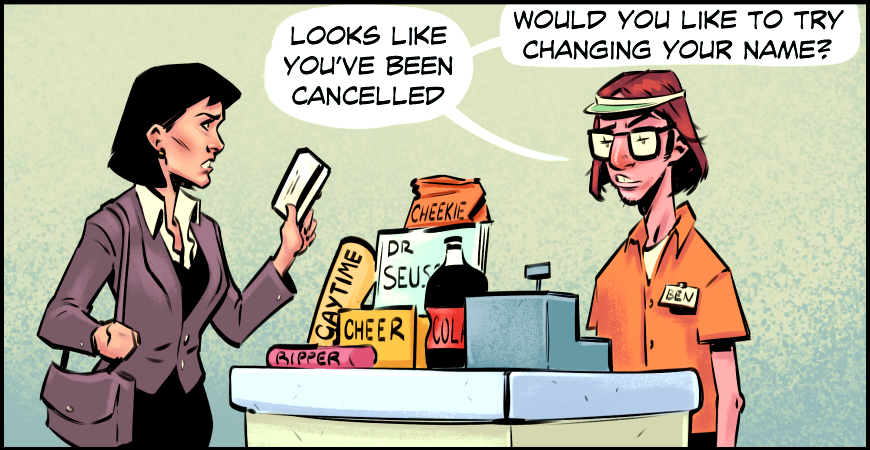

Consider the reaction from customers and the public when asked about the move to delete the “Golden Gaytime” brand, with 98 per cent voting to keep the name.

After seeing the positive reaction to their brand, Unilever said they had “a deep and longstanding commitment to help build a more diverse, equitable and inclusive society for all”. As you can imagine, the campaign to change the name was unsuccessful and this obscure ice cream has never been more popular.

The decade-long campaign to rename “Coon Cheese” was more successful, with the company, Saputo Dairy Australia, changing the brand name to Cheer earlier this year. Yet this was only done after extensive customer research, staff consultation, and academic research that showed the name had possible racist origins.

It may attract satire, but the name change was conducted carefully and in consultation with stakeholders, rather than as a reaction to online pressure.

It might be scary to be in headlights, but in the case of cancel culture, it’s often best to slow down, act strategically, and consult widely.

ReGen Strategic

ReGen Strategic