In the last sitting of Parliament, Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his Home Affairs Minister, Peter Dutton, unveiled a key component of their re-election strategy.

In comments that were subsequently withdrawn, Mr Morrison labelled deputy opposition leader Richard Marles a ‘Manchurian candidate’, going on to say the Chinese government had ‘picked its horse’ and was hoping for a Labor win.

The government argued that it was trying to focus voters’ minds on the choice they face at the election. However, former ASIO boss Dennis Richardson undermined this, saying the government was trying to create a perception of policy difference, where none existed, and that this was not in the national interest. Current ASIO director Mike Burgess said the weaponisation of national security was “not helpful”.

But the attack appears to have penetrated, to a degree, with right-wing front Advance Australia erecting billboards depicting China’s President Xi Jinping casting a vote for Labor at the ballot box.

It is conceivable that right-wing minor parties will also head down this path as the election approaches, seeing it as an opportunity to harvest the votes they need to cobble together quotas in the Senate.

So, how did we get to a point where a government that rates itself on national security is pursuing an election strategy that intelligence chiefs judge likely to undermine our national security?

The answer lies in the polls, and the fact that, with just two months until the likely election date, they are pointing to a landslide Labor victory.

Public polling data aggregated exclusively by William Bowe at The Poll Bludger for CGM Communications shows support for the Morrison Government has tanked since the end of last year.

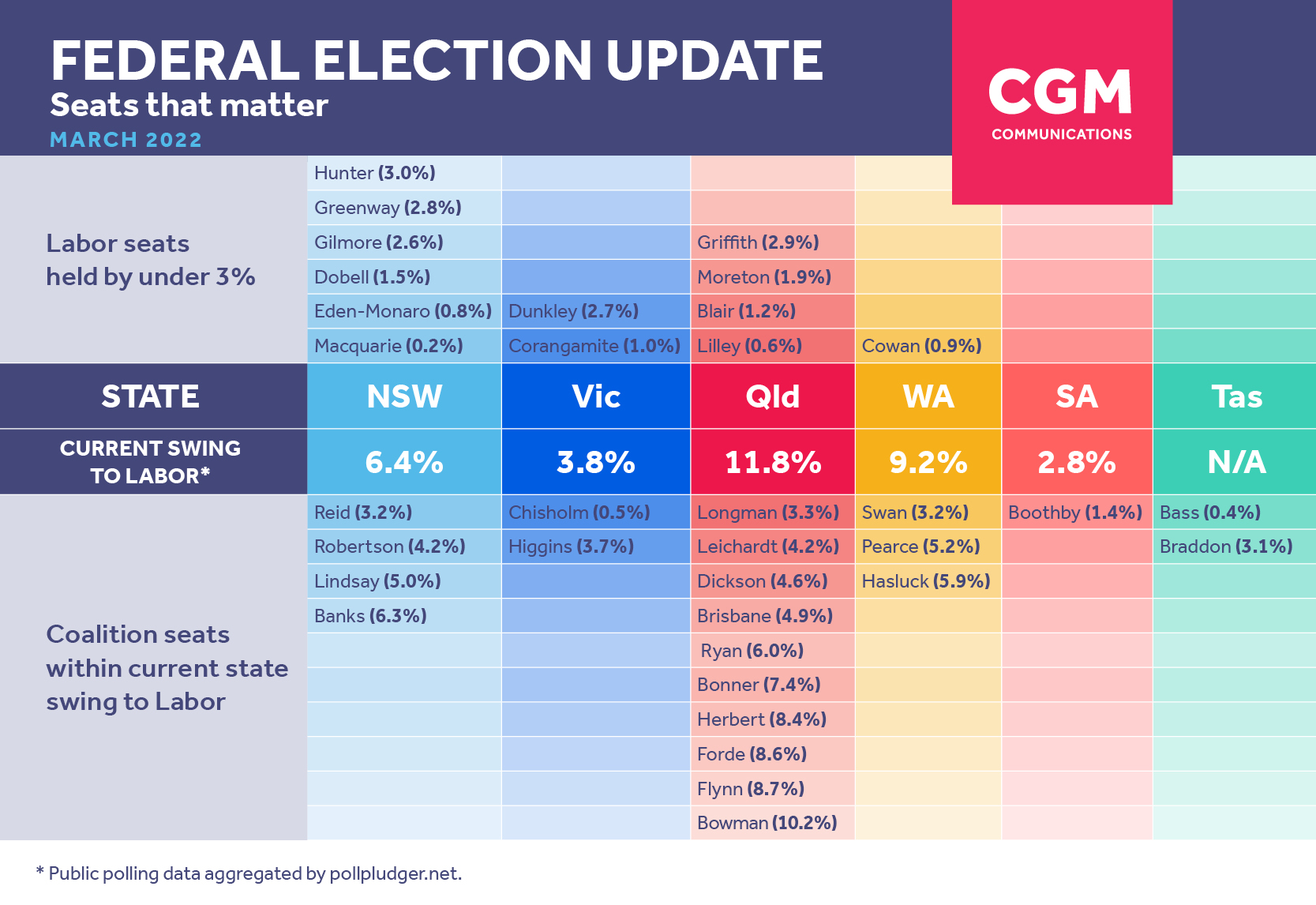

The Coalition’s position has deteriorated everywhere. Since the beginning of October, the movement has been 2.8 per cent in Labor's favour nationally: 3.3 per cent in New South Wales; 2.3 per cent in Victoria; 3.5 per cent in Queensland; 3.6 per cent in Western Australia; and 0.3 per cent in South Australia.

The swing to Labor is now 7.7 per cent nationally, with state-by-state swings ranging from 2.8 per cent in South Australia up to a massive 11.8 per cent in Queensland. In Western Australia, the swing is currently 9.2 per cent, with Labor set to win Swan (3.2 per cent), Pearce (5.2 per cent) and Hasluck (5.9 per cent), if this swing eventuated on election day.

Of course, polls are just a measure of sentiment at the time they are taken, rather than a prediction of an election outcome.

However, if the state-based trends currently observed were realised on election day, Mr Albanese would likely pick up 22 seats, far more than the seven he needs for a majority.

You can understand why Mr Morrison is breaking the glass and reaching for a national security debate, a strategy that, while often divisive, has proven successful at several previous elections.

Going back to the 1950s, as the fear of communism spread around western countries, the Menzies government found long term success in making the most of internal divisions within Labor at that time, in what became known as its ‘reds under the bed’ strategy.

After Gough Whitlam’s groundbreaking visit to China to meet with then-Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1971, Mr Whitlam became the first Labor figure branded a ‘Manchurian candidate’, a term borrowed from the 1959 political thriller novel of the same name.

Of course, Mr Whitlam went on to win the 1972 election and establish diplomatic relations with China, a move which contributed significantly to the decades of economic prosperity that followed.

Then, in 2001, the Howard Government, trailing in the polls, made the most of the highly inflamed post-9/11 environment by making asylum seekers and border protection front and center of its successful re-election push. Tony Abbott returned to this theme as opposition leader in 2013, ahead of his landslide win.

Whether Mr Morrison’s strategy is successful this time around may depend on the future trajectory of the Ukraine conflict. However, the Liberals would be worried by recent polling from Essential, which had voters preferring Labor to manage the relationship with China, and evenly split over who was better to understand and respond to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In an ideal world, the Australian body politic would be able to have a mature discussion about geopolitics, Australia’s place in the world and our vision for the future. But pre-election periods in Australia are rarely an environment for considered conversations.

As we’ve discussed, Australian political history has a number of examples of our better angels being silenced in the leadup to an election. And we’re not alone in this. In US politics, the Trump Republicans spend most of their time talking about illegal immigration and China. And the Democrats have long suggested Mr Trump is too close to Vladimir Putin, with the term ‘Manchurian candidate’ sometimes thrown around, in that context.

With the Morrison Government up against it and an inflamed global security environment, it looks like our better angels will struggle to find their voice again. It’s going to get ugly.

ReGen Strategic

ReGen Strategic