It was a calculated communication to his white, culturally conservative, working class base that was simultaneously designed to elicit a response from his enraged opponents that pushed his supporters further into his arms in an election year.

To many of us, it looked like madness. How could tear gassing your own citizens to clear the way for a photo opportunity at a time when Americans are suffering from both the health and economic impacts of COVID-19, as well as deep emotional pain at the killing of George Floyd be anything but electoral suicide?

To understand Trump’s thinking, we need to understand two realities. First, Trump is in deep political trouble. Second, motivating white, working class people to vote is his most plausible path to another come-from-behind victory.

But, first to Trump’s political problems.

The dominant narrative following Trump’s surprise victory over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election was that a surge in support from white non-college educated (working class) voters propelled Trump to victory in former industrial states that had traditionally voted Democrats.

Like most narratives, this represents only part of the story.

Trump’s victory also relied on college-educated Republicans, despite serious misgivings, holding their nose and voting for Trump over the even more unpalatable former Secretary of State, as well as African American voters not turning out to support Clinton at the same levels as they had to support Barrack Obama in 2008 and 2012.

According to modelling undertaken by the Centre for American Progress and FiveThirtyEight following the election, Trump wouldn’t have won in 2016, if any of these three conditions hadn’t been met.

Which is where Trump’s re-election problems begin.

In the highest turnout midterm election in more than 100 years, Democrats swept to a majority in the US House of Representatives. Their largest gain in seats came in traditionally Republican suburban districts that not only voted for Trump in 2016, but also voted for Mitt Romney, the Republican candidate for President, in 2012, with this swing delivered by largely college-educated, predominantly female former Republicans.

At the midterms, Trump lost a chunk of what used to be the Republican base, and there has been no evidence yet that he is winning it back.

Trump’s problems are magnified by the outrage among African Americans at systemic racism and their ongoing brutalisation at the hands of police, which was made most visible by the killing of George Floyd. The fact that both the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 are disproportionately impacting African American communities will be compounding this rage.

In this environment, the sharp decline in African American turnout experienced in 2016 may well be reversed, particularly if Democrat Joe Biden picks an African American as his running mate, which he is reported to be strongly considering.

As things stand, two of the three foundations of Trump’s 2016 victory are wobbly. Which is why Trump is seeking to reinforce the third - his base.

More than any other politician, Trump understands both the angst and potential political power of the white, American working class.

In their well-researched book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of American Capitalism, Anne Case and Angus Deaton describe how Americans without a college degree have few prospects in an economy where globalisation and technology are taking lower-skilled jobs. This has led to social decay and falling life expectancy in white working-class communities, on the back of rapidly increasing levels of suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol related illness – the deaths of despair.

Trump’s strategy in 2020 is the same as it was in 2016, being to position affluent, university educated Democrat politicians and journalists as elites who care more about ‘minority issues’ than they do about American workers, offering himself as the only one who understands the latter’s plight and, therefore, as the only one who can reverse it.

With white, non-college educated Americans representing about 40 per cent of the electorate, and historically having the lowest turnout rates at Presidential elections, Trump sees new voters and a path to victory in the family and friends of the people who voted for him in 2016.

Will Trump’s strategy be successful? There are signs, on the ground and in the polls, that some of his people aren’t buying what he’s been trying to sell in recent weeks. But, even if they did, whether this would be enough to offset what promises to be a much higher turnout rate among African Americans and any further drift of college educated Republicans to the Democrats is unknown.

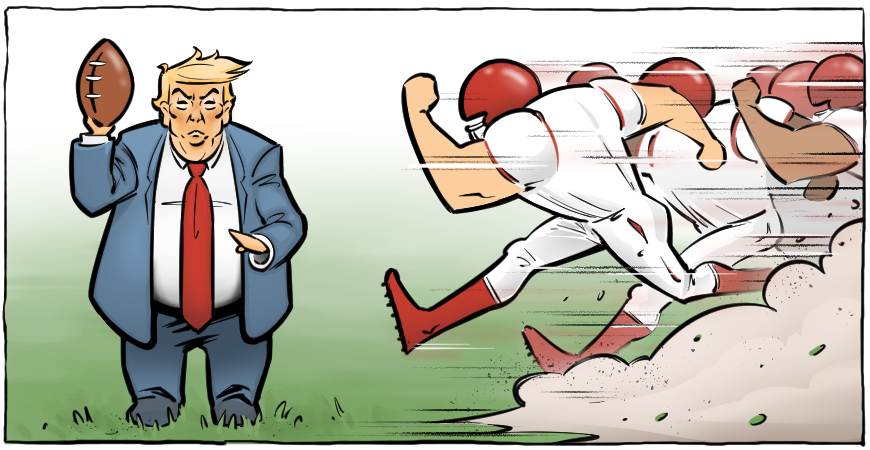

One thing is certain, should Trump be re-elected in November, he will see his base as having delivered it and his Hail Mary law-and-order play as the start of his comeback. Draw your own conclusions about what this would mean for the tone and substance of a second Trump term.

Daniel Smith is executive director and founder of CGM Communications.

ReGen Strategic

ReGen Strategic