It takes a spectacularly flawed government to lose an election in the COVID era.

It’s a feat that only Donald Trump has managed to pull off.

For the most part, incumbent governments across the democratic world have been returned with increased majorities, taking advantage of the platform and opportunities to demonstrate leadership that the pandemic has provided.

Voters appear willing to give credit where it is due, but withhold harsh judgment on missteps, given COVID, itself, isn’t any individual’s fault.

Take, for example, the current popularity of Boris Johnson’s conservative government in the United Kingdom. Despite bungling the early months of the pandemic and overseeing almost 130,000 COVID deaths, Johnson is now streets ahead in the polls. This is driven by an increasingly successful vaccine rollout, as well as the reality that the working-class support Johnson secured through Brexit never really left him.

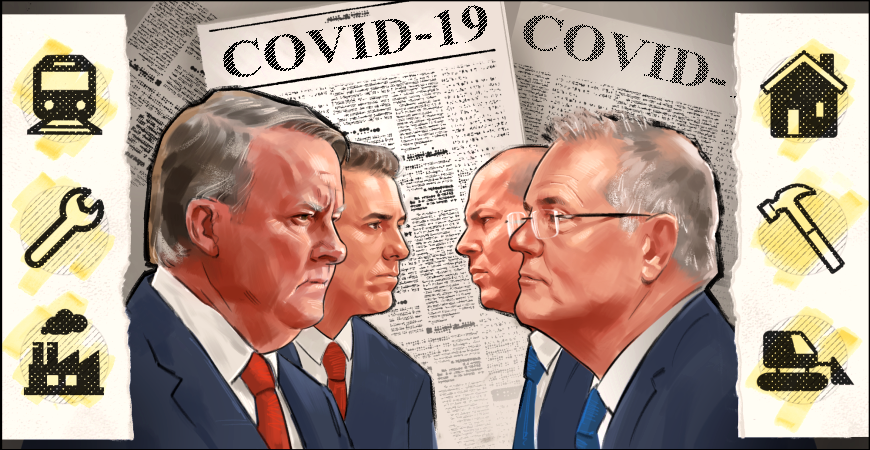

If you apply this post-pandemic political paradigm to Australia’s current federal political environment, it is hard to see the Morrison Government being defeated when it goes to the polls some time in the next 12 months.

While Australia’s island geography and a lot of heavy lifting by state and territory governments have contributed to the country’s strong COVID performance, the reality is that Australia is at the top of the pile in terms of its national COVID performance, both in terms of health and economic outcomes, and the Morrison Government would, quite rightly, expect to get some credit for this.

However, being in Canberra with clients for the budget this week, I didn’t detect the sense of inevitability about the election outcome among either Liberal or Labor operatives that you might expect in this pandemic political paradigm.

Labor figures genuinely feel they’re in with a shot. They point to the polls having had the Coalition and Labor neck and neck throughout most of the pandemic period, with the Prime Minister having had trouble converting the opportunities the pandemic has presented him into obvious electoral support.

With Mr Morrison failing to generate similar levels of support that many state and territory leaders have enjoyed during the pandemic, Labor concludes there is a drag on the Coalition vote and attributes this to non-COVID issues like bushfires and Parliamentary culture, as well as to COVID-related challenges, such as the undermining of state border closures, not taking responsibility for quarantine and the slow vaccine rollout.

Labor figures also point to the fact that the last two elections have been decided hand to hand, state by state, electorate by electorate, with a divided electorate delivering successive close results. And, when they take you through each state, seat by seat, they make a compelling case as to why the Coalition may have challenges on the ground.

And the Liberals I spoke to this week tend to agree.

The big questions coming out of budget week are whether either the budget or Anthony Albanese’s budget reply will shift the dial, when the election will be and who will win.

To borrow some Howard-era phraseology, Josh Frydenberg’s budget has clearly sought to scrape some barnacles off the ship of state. The question is whether the quantum of funding put into areas like aged care, childcare, mental health or women will be enough to make a lasting difference, or to convince wavering voters the government has a genuine commitment in these areas.

Anthony Albanese has clearly sought to establish another major theme to his platform, with a $10 billion housing future fund set to fund a continuous build of social housing across Australia. With a $15 billion manufacturing fund already announced, as well as a long-term commitment to extend childcare subsidies to all Australian families, Labor’s agenda is taking shape, with some clear points of difference to the government.

However, modern elections are increasingly fought on the issues of health and jobs.

With the Medicare wars all but over, vaccines and quarantine will be the terrain on which the health battles are fought at this election.

On the issue of jobs, the government is pinning its hopes on private housing construction, investment tax incentives for business, infrastructure spending and personal tax cuts giving taxpayers more money to spend with local businesses.

Until the budget reply, Labor’s jobs pitch focused on growing local manufacturing and sovereign capability in areas such as rail manufacturing. The continuous social housing build announced by Mr Albanese, inclusive of commitments on apprenticeships, was another significant commitment. I expect we’ll see similar initiatives in renewable technology and manufacturing in the months ahead. How Labor frames any decisions it takes on tax will be critical, both in terms of how it will affect people personally, but in how it can be framed by the Liberals as impacting on the broader economy and job creation.

As to when the election will be, the building consensus is that the Prime Minister will move once the vaccine rollout has reached critical mass, perhaps at two thirds of the population, so as take advantage of the strong economic conditions and to minimise the chance of new issues taking the government off course. This makes an election this year very possible.

As to who will win, there’s still a lot of water to go under the bridge. Given Australia’s COVID performance, the election remains Mr Morrison’s to lose. But, there are enough reasons not to rule out a surprise Labor victory.

Game on.

ReGen Strategic

ReGen Strategic